Digital Violin

The Violin is Dead

Long Live the Violin

IVAN MAKHONINE (1930)

VIOLON ELECTRIQUE

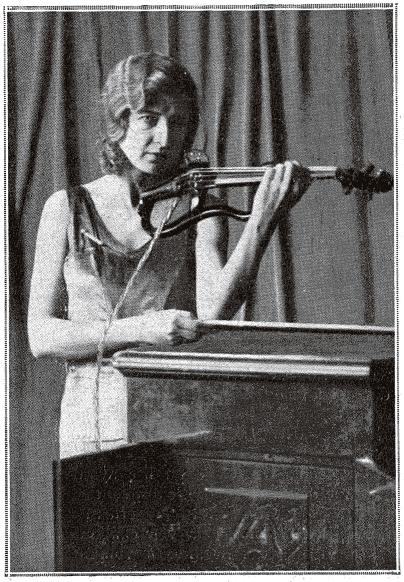

from "L'Illustration", April 12 - Paris, France (photograph showing Cecilia Hansen and the Makhonine violin)

Adopting techniques used for radiophonic or phongraphic loudspeakers, Mr Makhonine created a curious device to reinforce the sounds of the violin about which we asked our collaborator Honore for some technical explanation and our collaborator Vuillermoz for his impressions as a music critic.

.

One knows that the transmission of sound takes place by the movement of the air molecules around the point where the sound is produced. Now, the very fine surface of a string moves only few neighbouring molecules; it does therefore produce by itself only very weak and musically insufficient oscillations. To remedy this problem, one resorts to the phenomenon of the resonance.

Certain materials, wood notably, vibrate with an extreme ease. Through the points of attachment, and especially through the bridge, the vibrations of the strings of a violin are transmitted to the body which, by menas of this broad surface, transmits them to the surrounding air. Let us abolish the body of the violin, keeping only that necessary to support the bridge and strings: the bow will draw only almost indiscernible sounds.

Now, let us dispose on this outline of a violin a pick-up the top of which touches the bridge and which a wire links up to an amplifier: of this amplifier will go out considerably amplified the tiny sound born under the bow. The notes of the ordinary violin will take the extent(?) of those of the cello.

To what extent can the purity of the sound reconcile itself with the amplification? It does not befall on me to appreciate it musically. But, if one considers the thing from a technical point of view, it seems obvious that the sounds have to be subjected to a more or less considerable distortion. Some claim that by filtering the electromagnetic vibrations with appropriate devices(?) which, having arrived to the final point of their running, reproduce sound vibrations, one obtains an amplified sound purer than the initial sound. It seems very difficult, if not impossible that it be thus. The filters protect mostly against unwanted vibrations; if, by selecting the vibrations according to their frequency, they favour the quality of the reproduction(?) through the loudspeaker, they are unlikely to contribute to improve the original sound, which, besides, does not need it when it is issued by an artist having a good instrument.

Beides, techniques of the same type have already been applied abroad. In Berlin, notably, the conductor Deka would have succeeded in augmenting by about a fifth the sonority of an orchestra of six musicians. But these German artists use normal instruments with the resonating body, and the original sound adds to the electrically amplified sound.

F.H

Since the Electrical fairy became musician, one does not know any more where its music mania will stop. Not contented with the transmission by waves or by engraving on waxes of the concerts that the humans give, she got it into her head to become herself a virtuoso and goes as far as creating for her own use new instruments. After the Pianor, after the device of Martenot, after the vibrating Radiotone, here is the electric violin which, instead of transmitting the vibrations of its strings to a small varnished wooden box, entrusts them to a fluid which amplifies them and makes them bloom in a loudspeaker.

This broadcasting and this enhancement induces, as always, a light modification of timbre. The amateurs of speaking machines know only too well this sort of transfiguration that the string instruments undergo, instruments whose sound can enthuse up to the lyricism of wind instruments. Just like the lightly touched string creates harmonic sounds that seem to come out of a flute, all the same, certain violin notes, inflated by the electricity, resemble the timbre of the oboe, the cor-anglais or saxophone. One feels that a more powerful force than the human arm gives to these sounds a supreme continuity and balance. One loses the sensation of effort and is surprised by the ease with which the strands of horsehair generates an ample and vigorous melody that can dominate a whole orchestra and fill the vastest concert hall.

This dissemblance of timbres also poses a curious problem. What we call the sonority of the violin is a purely empirical acquisition of the ear. We have had to create, for the convenience of our fingers, instruments whose scientific logic is often debatable. Nothing proves that the rational sound of an instrument will not have been revealed to us on the contrary by the electric fluid of which nothing limits the material possibilities.

Anyway, the electric violin is an impressively powerful instrument out of which composers will be able to draw new and moving effects. It will be necessary, of course, to fight against the inherent difficulties of any amplification, that is to say against the magnification of all unwanted noise which accompanies the production of sound. The pick-up, while allowing us to study an amplified note, enlarges at the same time the squeak of the bow, its rebound and the amplitude of the vibrato, just like it accentuates the scratching of the needle on a disc. But one will certainly find the means to lessen these incidental noises and the musicians will then have at their disposal a whole new orchestral equipment which the traditionalists will curse but which will undoubtedly allow future composers to give us unforseen masterpieces, using unsuspected elements of emotions.

.V. (?Emile Vuillermoz, music critic?)

translated by Catherine Phillips & BAH (2006)

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 2.5 License.

up